Both hydropower and conventional thermal combustion electricity is depleted in a hotter new climate.

A new paper published at Nature Climate Change, Power-generation system vulnerability and adaptation to changes in climate and water resources provides a comprehensive look at how two categories of power generation will be impacted by climate change on a global level.

The study looked at both thermal power stations (that depend on the combustion of fossil fuels, biomass or uranium), and also at hydropower systems.

Hydropower relies directly on abundant flow in falling water from mountain snow melt, while each type of thermal energy requires a lot of water to boil to make steam to drive turbines, and water to cool off the boiled water as it is discharged.

Unlike solar PV and wind power, thermal electric power stations are totally dependent on adequate water supplies, at cool water temperatures

The study assesses how much global power generation will be at risk by 2050 under two alternative greenhouse gas emissions scenarios, one in which temperatures are able to be kept under 2 degrees C, and the other in which they continue to increase at current rates to a 2.5°C to a 5°C degree world.

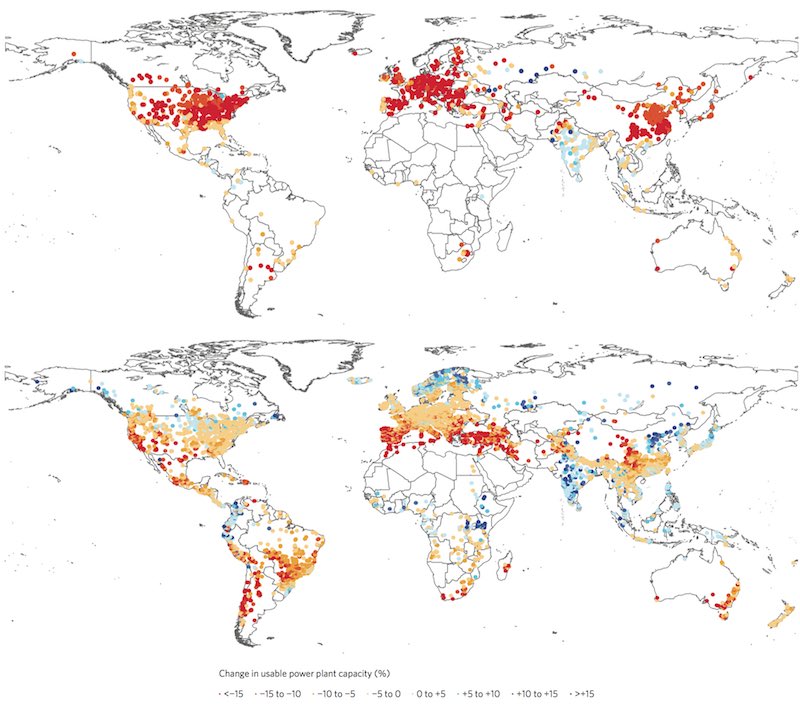

Impacts of climate and water resources change on annual average usable capacity of existing traditional power stations (upper map) and hydropower plants (lower map). Results are for the 2050s (2040-69), under a high emissions scenario (RCP8.5) and relative to 1971-2000. Source: Power-generation system vulnerability and adaptation to changes in climate and water resources.

The estimates in the study are based on an assumption that 80% of the world’s electricity is generated thermally – coal, gas, nuclear, biomass – with an additional 17% generated using hydropower. (Only 3% of global energy comes from PV and wind, according to the study*.)

(*The figures originated from a 2009 paper from the IEA – so it’s based on 2008 data. The IEA has been fairly notorious for undercounting renewables for some time, as the adoption rate has increased exponentially, so in the future, it is unlikely that 80% will still be thermal.)

As of now, however, of all water taken from rivers and lakes; the percentage used in thermal power generation amounts to about 50% in the UK and about 40% in the US.

With so much electricity generation so dependent on water, the study shows just how vulnerable is the world’s combustion-based energy supply in a hotter, drier world, when water will be warmer and droughts and heat waves longer and more frequent in many regions.

The paper is one of several that look at the impact of a hotter climate on thermal electricity generation, between coal, gas, biomass and nuclear. Two more quantify the effects on electricity costs.

How rising temperatures cause rising cost: droughts reduce cheap hydropower

As Californians have just experienced, hotter temperatures have already begun to result in the droughts long predicted for the entire Southwest US by climate scientists as the 21st century continues to warm.

What California has just seen is that when droughts deepen, mountain reservoirs and lakes and rivers dry up, and hydropower dries up with them.

A Pacifica Institute study quantified the costs as California’s hydropower declined, raising average electricity prices as a result – by $3 billion.

In early 2016, the Pacifica Institute put out an assessment of those effects Impacts of California’s Ongoing Drought:Hydroelectricity Generation provided a comprehensive assessment of the costs to California of lost hydroelectricity.Hydropower had provided about 18% of California’s electricity. But as the drought wore on, creating longterm water shortfalls, that was reduced by almost half from the end of 2011 till the end of 2015. By 2015, with the state’s reservoirs and ground-water levels nearly depleted, hydropower provided less than 7%.

The hydropower shortfall was replaced with gas, which is not only more expensive than hydropower, but also more polluting

“Assuming the marginal costs for electricity during the 2007-2009 drought were approximately the same as between the 2012 and 2015 water years, the full additional costs to California electricity customers of seven years of drought were a reduction of 85,000 gigawatt hours (GWh) of hydroelectricity and an increased cost exceeding $3 billion,” said the report’s author, Pacific Institute President, Yale hydro-climatologist Peter Gleick.

How thermal power is reduced as water temperatures increase:

The changes that higher temperatures bring not only deplete water flow, impacting hydropower, but also act to warm the water that is needed to cool discharged water from thermal power plants. This warmer water, both in rivers and the ocean, also reduces electricity production.

Because of rules governing environmental degradation, thermal plants that essentially boil water must shut down if the water used for cooling gets too warm.

Discharged water temperature is monitored to ensure that coal and nuclear plants don’t discharge water that is too hot, endangering wildlife in surrounding waterways.

But already in 2007, during a heat wave that contributed to river water reaching an astounding 90 °F, the Tennessee Valley Authority had to shut down a nuclear plant due to hot river water in Kentucky.

During the heat wave in Europe in 2003 and 2006; 17 nuclear plants across Germany, France, Spain and Romania had to idle production or shut down entirely because the waterways normally used to cool down boiled water coming out of the electricity plants was too warm to discharge hot water into.

Shutting down or idling plants reduces generation and raises electricity prices because the lowered output of electricity results in higher prices per unit of generation

Paper assesses global costs of thermal generation in a hotter water future

In a third paper published at Norges Handelshøyskole, Electricity Prices, River Temperatures and Cooling Water Scarcity, a future of higher costs for thermal electricity is predicted as a direct result of the warmer water temperatures caused by climate change. In the longer term, these costs could become unsupportable.

The study co-author Øivind Anti Nilsen estimated that even as little as a one degree rise in average river temperatures will result in almost a 4% percent increase in electricity prices, over the course of a week.

“The analysis shows that higher temperatures lead to reduced production in power plants and hence higher electricity costs. Prices shoot up”, explained Nilsen, a co-author of the paper, and professor at the Department of Economics at Norges Handelshøyskole.

“The higher the temperature, the lower the power plant’s efficiency. Prices therefore rise in line with the temperature,” said Nilsen

“Many people who work on the effects of climate change have overlooked these price effects and their implications,” he said.

These increasing costs of climate change will be felt in the US as much as in Europe, because in the US, the thermal energy industry accounts for as much as 40% of all freshwater withdrawals, according to the US Department of Energy

This effect will only continue to increase in the future, as the world sees more frequent and hotter heat waves. Yet the world continues to build thermal plants that are dependent on a diminishing resource – cool water.

The Arabian Gulf region already has one of the highest ocean temperatures in the world, reaching above 95°F in the summer. Despite this inability to act as a cooling resource, the Arabian Gulf is to provide the cooling for two proposed nuclear plants, a 1 GW nuclear plant from a Russian manufacturer, and another much larger one, comprising four adjoined 1.4 GW units, that is made in Korea.

So, which regions will be most affected?

“In particular the US, southern South America, southern Africa, central and southern Europe, Southeast Asia and southern Australia are vulnerable regions,” said Dr Michelle van Vliet, a researcher at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and lead author of Power-generation system vulnerability and adaptation to changes in climate and water resources.

“This is because declines in mean annual streamflow are projected combined with strong increases in water temperature under changing climate.”

One more reason to abandon thermal combustion for making electricity.

Image credit: via FlickR under CC license