NEWPORT, Ore. — We bounced over four-foot swells outside Yaquina Bay, speeding along in Crackerjack, Capt. Jack Craven’s 43-foot charter. It was a calm early September day by the rambunctious standards of the Oregon coast, a stretch of the North American continent frequently battered by waves taller than your house – even if you live in a two-story. But even a quiet Pacific pulses with awesome power.

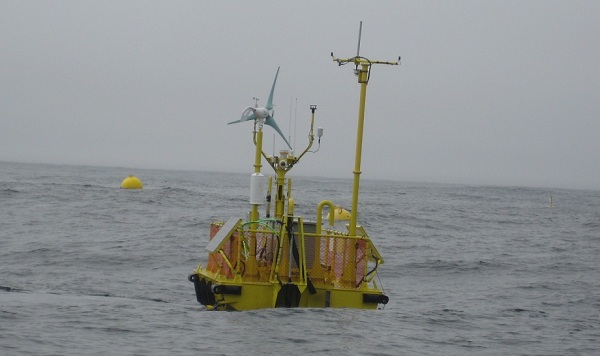

“If we could just grab a tiny piece of this energy,” I found myself thinking – an unoriginal thought if there ever was one. The idea of pinching off a little Pacific power has excited interest for years, and had in fact led to the development we were headed out to see: the Ocean Sentinel test pod and its temporary companion, the New Zealand born and Oregon schooled wave energy converter called WET-NZ.

A handful of scientists from the Northwest National Marine Renewable Energy Center at Oregon State University, who put the Ocean Sentinel in the water, was aboard the Crackerjack, along with Justin Klure, an executive at Northwest Energy Innovations, the Oregon company that retooled the Kiwi WET-NZ into the second-generation, half-scale test model being put through its paces 2.5 miles northwest of Yaquina Head.

Reporters were along for the ride, as well, most of them getting their introduction to this new wave energy thing that suddenly was being talked about in Oregon in a big way – bigger, perhaps, than it really ought to at this point.

Earlier this month, The New York Times wrote a story about the planned upcoming deployment of an Ocean Power Technologies wave energy converting buoy off the coast near Reedsport, about 70 miles south of Newport. Shortly thereafter, The Oregonian, the Portland media heavyweight, editorialized breathlessly that because wave energy might prove to be a “runaway success at sea” like the “near-overnight sensation of wind farms,” state regulators needed to “get ahead of the wave power rush” that “could test Oregon’s capacity to plan and regulate ocean use to the satisfaction of multiple stakeholders and for the protection of fisheries and marine ecosystems.”

Whoa. Deep breath, Oregonian.

The wind power that became a “near-overnight sensation” had been operating commercially and at a large scale in California for decades before it busted out in Oregon. All renewable technologies are constantly evolving, but the basic format of wind power was long well-established before the boom of the past several years.

Wave? It’s commonly said that wave energy is in its infancy, but that might be overstating its development. Conception has occurred. The fetus is growing. Birth? We haven’t gotten there yet.

“We’ve got so much to learn,” Sean Moran, manager of the wave energy ocean test facilities for NNMREC, told me dockside before we headed out to sea. “There are tons of different designs that function very differently. We don’t really know what’s going to work and what isn’t – there’s a lot of work to do.”

Not that Moran isn’t excited – he’s in the field because he’s jazzed about the possibilities. But what was clear from the NNMREC and OSU scientists was that even more than hoping to help wave energy developers improve their wares, they’re interested in making sure wave energy unfolds in Oregon in a way that doesn’t screw the environment, commercial fishers and crabbers or those who use the ocean for recreation.

The OSU researchers are monitoring electromagnetic fields and acoustical impacts, as well as effects on sediment, invertebrates and fish.

“This is why we’re here,” Moran said. “It’s an opportunity to learn, to go forward in a way that makes sense for all the stakeholders here. Wave energy is just one player and it’s going to have to fit into a complex picture.”

A representative of the Oregon Anglers told The Times, “Our greatest concern is that they don’t do what they did with dams — put a lot of them in the ocean and then just stand back and see what happens.”

Anglers and others are wise to keep a close eye on the wave developers, but the difference in pace and scale between what’s going on with wave energy and what happened with Northwest dam building is night and day.

Out of nowhere in the 1930s, Roosevelt’s Bureau of Reclamation built the biggest structure in the history of the world when it made Grand Coulee Dam (without fish ladders, by the way, robbing the Colville tribe of the salmon that were the centerpiece of their culture). By 1984, there were 14 dams on the Columbia, and more than that on its tributary the Snake, forever changing ecosystems on a massive scale.

There is very little chance of wave energy having that irretrievable impact on the ocean. Even if the industry were ready, there is no Roosevelt to put thousands of wave energy converters in the ocean. This is an industry — a fascinating, exciting industry, but also a wannabe industry — that is inching along.

The New Zealand group behind the WET-NZ deployed a proof of concept device six years ago. Quarter-scale devices came five years later. Even if the Oregon arm of the project goes well, they’re still at least another iteration – with loads of testing along the way – away from nailing down their design.

And Ocean Power Technologies, yes, it will put a 150-kilowatt buoy in the water, weather permitting, in early October. It took OPT years to get its license from the feds to put 10 buoys in the water, but even that won’t happen until the first buoy survives and produces power for a year (and a grid connection won’t happen until then, at the earliest, as well).

And hanging over all this is the question of whether wave energy can be anywhere in the neighborhood of competitive in what could be a long era of cheap natural gas (and with solar and wind both falling in cost). Investors aren’t exactly flocking to it, and government support, already modest, doesn’t figure to blossom. OPT will need more help if it’s to get those other nine buoys in the water. The state-backed Oregon Wave Energy Trust is doing what it can, and the U.S. Department of Energy has been chipping in, but the years ahead do not figure to be flush times for the state government or the feds.

Meanwhile, everyone is watching. The fishing community, environmentalists, scientists – even some journalists. Out on the water earlier this month, it was hard not to feel the excitement about the great possibilities. But back ashore, the reality of the long, fraught process wave power faces is clear. Deep breaths, everyone.