As most school kids learn in elementary science class, dark objects tend to absorb the sun’s rays and heat up faster than light objects, which reflect more of the sun’s energy. Green building contractors know this concept well and have designed many “cool roofs” with white materials to moderate temperatures during the summer months. But do they know exactly how much they are saving in terms of energy costs?

A research team at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) in Princeton, N.J., set out to answer this question earlier this year, using their own buildings as guinea pigs. According to early results from the study, the thickness of a cool roof may have as much of an influence on energy savings and thermal performance as surface reflectivity.

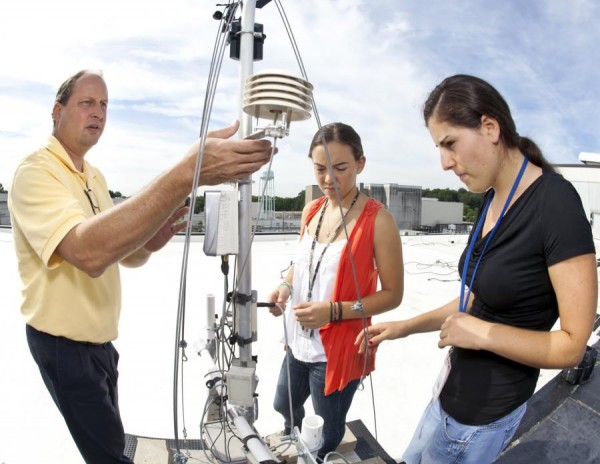

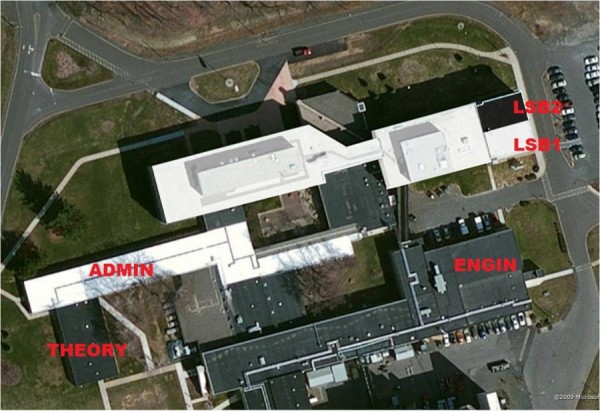

From March through September, Keith Rule, a senior project engineer at PPPL’s Environment, Safety, Health & Security Department, worked with a team of high-school interns to set up both black- and white-colored roofs atop PPPL’s flat administration buildings, using materials of varying thickness for each color. The team then installed an array of five weather stations at strategic spots on top of and underneath the roof. These stations employed 25 weather sensors to record the roofs’ thermal performance during the many weather extremes of the typical New Jersey summer and winter.

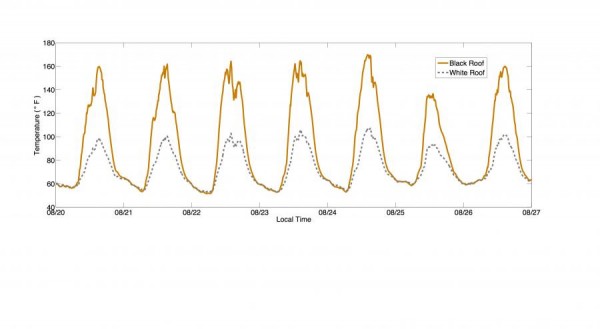

After about half a year—plus a few 85-mph gusts during Superstorm Sandy in late October—the weather stations survived the wind, rain and blazing sun to provide a wealth of data for the research team. As expected, white side stayed much cooler than the black side. When the thermometer hit the 90s in late August, for instance, the black roofs at heated up to between 130 and 170 degrees F, which was, literally, “hot enough to fry an egg,” PPPL noted. On the white side, the roofs stayed about as warm as the air, ranging from 90 to 100 degrees F.

The surprise, however, came when the team examined the “R-value,” or thermal resistance of the underlying roofing material. According to early data, the thicker the roofing material was, the less of an effect reflectivity had on temperature changes. This moderation in temperature extremes with the thicker insulation, the team said, appears to have the same effect in hot and cold weather.

PPPL’s cool roofs project is expected to end in January 2013. As the experiment continues into the winter months, the PPPL team will find out how the presence of snow, ice and freezing temperatures will affect the black and white roof sections. Because using thicker materials and adding more insulation costs more money than merely painting a roof white, the results could have a significant impact on how cool roofs are designed, as well as when and where they should be applied to green buildings.

Princeton University engineering professor Elie Bou-Zeid, the lead researcher on project, said this experiment may become one of the more comprehensive studies on cool roof concept, partly because it takes roof thickness into account and partly because of the enormous amount of data being collected. Every 15 minutes, the weather stations send measurements on temperature and heat absorption to Bou-Zeid and other researchers. This data is then compared with the real-time information on the electricity and fuel usage for the building’s HVAC system, he said, which will help researchers come up with a more accurate measure of year-round performance and energy costs.