The first device to hook in to the new wave energy testing site in Oregon is a New Zealand-hatched piece of machinery that was developed with the help of a $1,818,500 grant from the U.S. Department of Energy.

But before you get your knickers in a bunch over U.S. tax dollars backing Kiwi energy developers, rest assured there’s a big American component to this project. Northwest Energy Innovations, a Portland, Ore., firm, the actual recipient of the DOE grant [PDF], is a partner on the project and is leading the deployment of this second-generation device in Oregon.

And parts of the Wave Energy Technology-New Zealand device were built locally at Oregon Iron Works. (That’s the same company that’s been working on Ocean Power Technologies’ PowerBuoy, which is due to become the first grid-tied wave device to go into U.S. waters in the next several weeks.)

Testing of the WET-NZ, which is expected to last a couple of months, will help guide Northwest Energy Innovations in further developing the device — but it will do more than that, too, according to the Northwest National Marine Renewable Energy Center, based at Oregon State University in Corvallis.

“NWEI is blazing the trail for this industry in Oregon,” Sean Moran, NNMREC’s Ocean Test Facilities manager, said in a statement. “Through testing in our facility they are helping to answer core questions about wave energy for a broad community of stakeholders.”

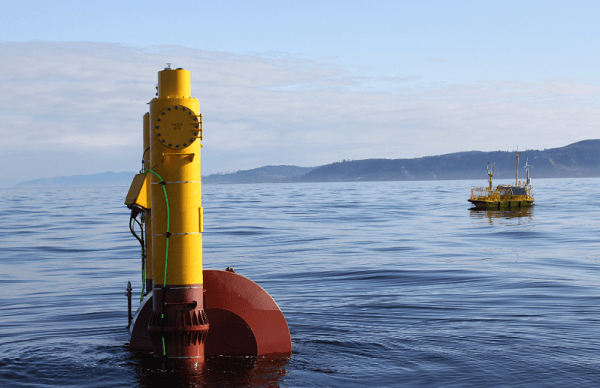

While it’s hardly small at 18.4 meters long, the WET-NZ — which was attached to the Ocean Sentinel tester off Newport on Aug. 23 — is a half-scale model. Earlier, Northwest Energy Innovations had worked with the NNMREC to test a one-thirtieth scale model at Oregon State’s Tsunami Wave Basin.

Those tests formed the basis for the specific design of the device now getting a workout in the Pacific.

“This is a huge milestone for the WET-NZ technology, for Oregon, and for the wave energy industry as a whole,” said Justin Klure, program manager for NWEI.

Like the PowerBuoy, the WET-NZ is in a class of wave devices known as “point absorbers.” As the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management explains, “A point absorber is a floating structure with components that move relative to each other due to wave action (e.g., a floating buoy inside a fixed cylinder). The relative motion is used to drive electromechanical or hydraulic energy converters.”

Northwest Energy Innovations says one aspect of the WET-NZ that makes it special is the ability of its float to rotate continuously and also oscillate back and forth. This allows the device to extract energy from both types of motion, the company says, while also making it less likely to be “over-stressed at the extremes of motion – an issue that has caused other wave energy technologies to suffer hydraulic ram failures … because by design they have to restrict the float motion with end-stops.”

“The survivability of the WET-NZ is something we think of a key advantage,” Klure said in an interview. “Obviously you want to maximize power production, but if you don’t have survivability, you’re at zero.”

Versions of the device have been tested in New Zealand, but one of the partners in the project told the New Zealand Herald that the Oregon test is a key next step in bringing the device to market – though not the final step.

Industrial Research Ltd’s Gavin Mitchell “said the next step after this test would be to get further funding from the U.S. government to develop and trial a full-scale version of the device,” which would require bigger, more powerful waves in another part of the country, the paper reported. But Klure said that might have been a misinterpretation of Mitchell’s remarks.

“Our waves in Oregon are as big and good as anywhere,” he said. The question would be whether the Pacific Northwest has the facilities for a longer-term test of a full-scale, next-gen version of the WET-NZ, something that wave power backers hope will be addressed with the Pacific Marine Energy Center, a grid-connected test center in the planning stages.