When it comes to renewable energy, wind and solar tend to make the headlines–but another form of green power is quietly gaining momentum on coastlines around the world: wave power.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, wave power encompasses various forms of technology designed to extract energy from waves on the surface of the ocean (or from pressure fluctuations below the surface) and convert it into electricity. Experts believe there is enough energy in the world’s waves to provide up to 2 trillion watts of electricity, but wave power isn’t feasible to extract in most places. The optimal areas for wave power generators include the western coasts of Scotland, northern Canada, southern Africa, Australia, and the northeastern and northwestern coasts of the United States.

The Pacific Northwest is considered especially rich in potential wave power, and Oregon in particular. Jason Busch, Executive Director of the Oregon Wave Energy Trust, told us, “Many places around the world have good wave energy resources, but not all places have the other essential features necessary to attract an industry.”

He believes that the Oregon has all the key factors, including an underutilized electrical grid infrastructure ready to take on more power, rising power demands from a growing population along the coast, and manufacturing capacity, as well as the infrastructure and port capabilities necessary to handle the transportation of heavy wave power equipment.

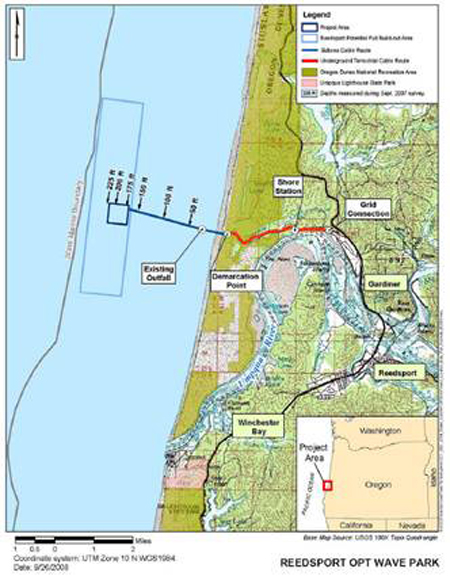

This wave power potential is fast becoming a reality at a wavepark off the coast of Reedsport, Oregon, which uses a hydraulic pump-style technology that lifts and plunges in accordance with ocean waves, generating electricity via kinetic energy.

This renewable energy project is currently in the environmental planning stages, but Ocean Power Technologies of New Jersey, which owns the project, expects to file a Final License Application with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission soon–which, if granted, will be the first such license ever issued for a commercial-scale wave power project in the U.S.

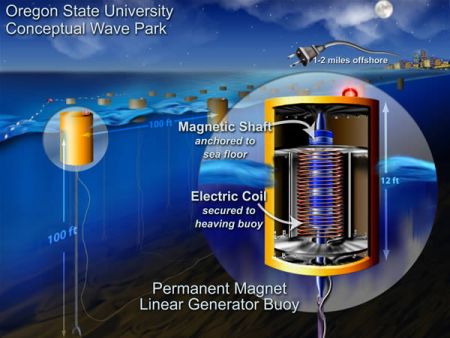

The wave power generators at the Reedport Wavepark are known as point absorbers–floating structures with components that move relative to each other due to wave action (e.g., a floating buoy inside a fixed cylinder). Other wave power technologies include terminator devices that extend perpendicular to the direction of wave travel and capture or reflect the power of the wave; devices built around an oscillating water column, in which water enters through a subsurface opening into a chamber with air trapped above it; attenuators, or long multisegment floating structures oriented parallel to the direction of the waves, and overtopping devices that feature reservoirs filled by incoming waves to levels above the average surrounding ocean, as in pumped hydro.

What are the major obstacles hindering the development of wave power? First, the fact that there does not yet exist a precedent for the licensing of such facilities–and second, the fact that when it comes to coastlines, there are a lot of stakeholders involved, including the fishing industry.

In looking to the future of wave power in Oregon and beyond, Busch emphasizes the necessity of public debate on how we use the nation’s coastlines, drawing lessons from the debate that rose up in the early nineties regarding grazing on federal lands.

“The cattle industry had built up a business model around free and unfettered access to the federal western lands,” he said. “What we learned from that debate, which ultimately ended up in the Supreme Court, is that the commons, in the form of federal lands, belong to the people, and the people ultimately must decide how the resource will be used. Just because we get used to using a resource in a particular manner doesn’t mean that we’ll always be able to use it in that manner.”

He goes on to note that as public needs change, the fishing industry may need to make room for other uses of the ocean, as determined by public debate.