Scientists at Stanford University have come up with a system to help blind people see again using retinal implants that operate like tiny solar cells.

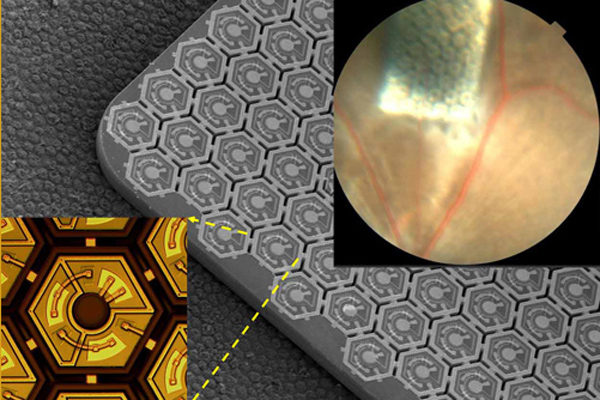

The photovoltaic (PV) chips, surgically placed under the retina, convert light into electric currents triggering signals in the retina, which then flow to the brain, enabling a patient to regain their vision.

The team from Stanford’s School of Medicine said the technology might one day help restore sight to people who have lost vision because of certain types of degenerative eye diseases.

The method for the system is quite ingenuous. Visual information from the outside world would reach the chip via a miniature camera fitted inside a pair of goggles, which the patient wears. The image captured on camera appears on a liquid crystal micro-display embedded in the goggles (which are similar to the goggles used by video gamers). The image would then be beamed from the LCD using laser pulses of near-infrared light to the photovoltaic silicon chip.

“It works like the solar panels on your roof, converting light into electric current,” Daniel Palanker, Stanford’s associate professor of ophthalmology and the paper’s senior author, said in a statement. “But instead of the current flowing to your refrigerator, it flows into your retina.”

The Stanford researchers are experimenting with the technology on lab rats. They have already used rat retinas to see how the photodiodes contained in the PV chips convert light into electric pulses. The scientists are now testing with live rats to see physiological and behavioral reactions. They are hoping to find a sponsor to support tests in humans.

The Stanford research, published in Nature Photonics this month, is not the first time scientists have attempted to return sight to blind people. A number of retinal prostheses are in development right now and at least two are undergoing clinical trials in Europe. Los Angeles-based company Second Sight’s device was approved last month for use in Europe. Another company, Retina Implant, based in Germany, has carried out clinical tests.

According to the company’s website, Retina Implants have successfully implanted 12 patients in the UK at centers in London and Oxford.

However, the Stanford team said most of the other devices being tested right now require coils, cables or antennas inside the eye to deliver power to the retinal implant. Because the Stanford device uses near-infrared light it obviates the need for wires and cables.

“The current implants are very bulky, and the surgery to place the intraocular wiring for receiving, processing and power is difficult,” Palanker said. However, because most of the hardware in the Stanford device was incorporated into the goggles the surgeon would only need to create a small pocket beneath the retina and then slip the photovoltaic cells inside it.

Co-authoring the study alongside Palanker was Keith Mathieson, Ph.D., a visiting scholar in Palanker’s lab, and James Loudin, Ph.D., a postdoctoral scholar. The technology was jointly conceived by Palanker and Loudin.