If you can read this, you’ve probably already survived the much-reported, thoroughly ridiculous Mayan Apocalypse prophecy as today marks the end of the “long count” calendar created by the ancient civilization. Real disasters, of course, are no joke, as we saw from the losses of $65 billion (and counting) from Superstorm Sandy this fall and $108 billion from Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Coastal cities worldwide are scrambling to prepare for many more “Storms of the Century” to come.

Some designers have responded with a bunker mentality, building homes that are partially underground, as was documented masterfully by TreeHugger. Others went the survivalist route, such as the Midwest-based Vivos, offering shelters that are a throwback to the atomic days of “Dr. Strangelove.” Recent studies, however, suggest that many passive green building strategies—in addition to reducing energy costs and slowing the drain on natural resources—can also soften the impact of natural disasters and make life more healthy and bearable for survivors during the recovery period.

Science writer and reproductive biologist David Bainbridge wrote recently on the Triple Pundit website about how green building is “one of the best antidotes to climate change.” Buildings, he points out, generate 40 percent of the global warming gases emitted in the United States and use 70 percent of the nation’s electricity. “If we do things right,” he writes, “we can cut energy use 90 percent in new buildings and 70 percent in retrofits while improving comfort and health.”

As he describes in his book, Passive Solar Architecture (Chelsea Green, 2011), passive systems are inherently flexible compared to conventional buildings because their form, materials orientation and thermal mass are designed to be as independent as possible from electricity, oil, gas, firewood or coal. These buildings, which often have their own PV panels and rainwater harvesting cisterns, are therefore “less brittle” when faced with storms, earthquakes, terror attacks or wildfires that can render a city helpless. Bainbridge continues:

“This is in great contrast with so many of today’s buildings that are unusable without their umbilical connection to the grid. These buildings are like people on an iron lung. Many don’t even allow natural ventilation because they have sealed windows. They are addicted to electrically powered heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems.”

Scientists say that as the climate slowly warms and melts the polar ice caps, storms even stronger than Hurricane Sandy will become more common and the shorelines of the city’s boroughs will be subject to more frequent and severe inundation. After the flood waters from Sandy slowly subsided, the New York/New Jersey region became the symbol of the expected rise in sea levels over the next century.

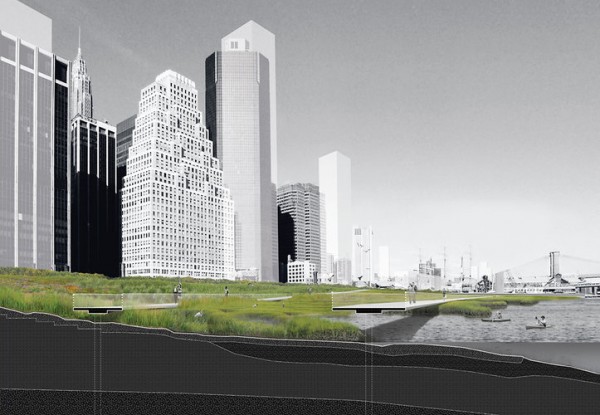

In response, architects Stephen Cassell and Adam Yarinsky, from the New York City-based firm Architecture Research Office, have devised an ambitious, but apparently feasible, plan to embrace the “new reality” of rising sea levels by restoring the natural barrier of wetlands around lower Manhattan that was lost during the industrial age.

Replacing the hardened seawalls with a buffer zone of tidal marshes, they say, will help absorb the energy of future storm surges and reduce flooding of critical buildings and subway tunnels. In addition, the plan calls for transforming some city streets into drainage channels, using semi-permeable paving materials and more trees at street level to direct excess water back to the harbor. Meanwhile, major sewer, gas and electric lines could be rerouted to waterproof chambers under the sidewalks.

In those cases where green buildings do get destroyed by natural disasters, the debris that is left behind also tends to be more benign that traditional building materials. Most contain low-VOC-emitting compounds and are made from natural, nontoxic substances.

The environmental testing firm EMSL Analytical recently alerted residents and cleanup crews picking through the damaged homes in the aftermath of Sandy that many of the structures were built before asbestos was banned as a construction material. Workers on those houses should beware of friable asbestos fibers in the air, which can cause lung diseases such as asbestosis, lung cancer or mesothelioma.

“Even the process of drying out one of these damaged buildings can release asbestos fibers into the air,” EMSL warned in a press release. “If not conducted properly, the drying process can result in airborne contaminants being spread throughout a property, even into areas not damaged by the storm.”

For more information on the potential health risks, EMSL has sponsored an educational video here about hazards that can result from property damage after a storm such as Hurricane Sandy. More information about testing for asbestos can be found at the Asbestos Testing Lab.