Would it cause irreparable and unnecessary habitat damage or is it a relatively benign price to pay in the fight against global warming?

That’s the question – again – as the quest for renewable energy in the Southwest United States continues to unfold. The latest project to get scrutiny is an energy storage proposal in California that would use billions of gallons of water sucked up from desert aquifers to create two reservoirs in the area around Joshua Tree National Park.

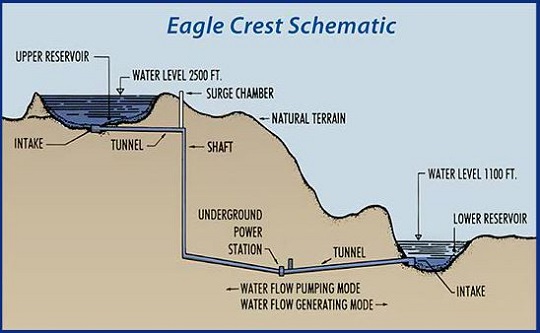

In a draft final water quality certification report, California regulators lay out conditions for the certification of the Eagle Mountain Pumped Storage Hydroelectric Project, which would turn two former iron ore pits, one 1,400 feet above the other, into reservoirs that could be used to store off-peak energy.

Here’s the lure of the project: Renewables often come when demand is low – like late at night or in the early morning hours for wind, or throughout the weekend for solar. The Eagle Mountain project would offer the possibility of shifting 1,300 megawatts of power production from when it isn’t needed (that’s when the power would be used to pump the water uphill) to when it is (that’s when the water would be released through turbines).

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission considers “pumped storage projects to be capable of providing a range of ancillary services to support the integration of renewable resources and allow for more reliable and efficient functioning of the electric grid.” FERC has seen more such projects enter into the application process, but getting them through the process and actually built is a long road — the Eagle Mountain project has been kicking around for at least five years. Costs are a concern, but so too are environmentally impacts.

The Eagle Mountain project has generally been characterized as environmentally benign because it is a close-looped system on already marred ground, but Rewire blogger Chris Clarke, an expert on the impacts of renewable energy projects on the desert, says there are issues to consider.

Like all projects, this one would require moving earth in its construction – both at the site, and in developing the transmission lines that will feed power to and from the facility. That could be a problem for the desert tortoise, a species already stressed by renewable energy developments in the desert, like the Ivanpah power tower project.

The Eagle Mountain project would also require water to be sucked up from the Chuckawalla Valley Groundwater Basin – 32,000 acre feet of water (that’s 10.6 billion gallons) to initially get the system up to full capacity, but with seepage and evaporation, over 50 years of operation the total groundwater need would be 110,000 acre-feet.

Which brings up another issue: The impact of creating acres and acres of surface water – for the reservoirs and for various brine ponds that would be needed – in the desert. One major concern is that it could lead to an increase in the raven population, which could pose its own threat to the desert tortoise.

The draft final water quality certification report was released last Tuesday and is open to comments until noon on April 10. See the first page of the 54-page PDF for more info on submitting a comment.