The Passive House standard is catching on exponentially in the US, but we’re still way, way behind Europe, where passive house construction is not only common but actually required by code in parts of Germany and Belgium. A new book, The Greenest Home: Superinsulated and Passive House Design, will help spread the word.

This medium-format book succeeds as eye-candy while at the same time it has enough drawings and blower door test results to engage the Passive House geek. The author is one herself: architect/professor Julie Torres Moskovitz designed the first Passive House (PH) retrofit in New York, which is one of the 18 houses featured in her book. She definitely knows her stuff.

Retrofits, low-budget houses, and low-income multi-family housing are all challenges that relatively few PH projects have taken on in the US, and I’m glad to see each of them among these 18 case studies—houses located in the northeastern US, western Canada, Belgium, Switzerland, France, Japan, and Kansas.

For each study, we get a couple of pages of text presenting details, plus several pages of color photos. An appendix section gives each house an additional two pages of energy performance data, work-in-progress photos, and cross-section detail drawings of wall, roof, and floor. I really appreciate those, since they’re at the heart of what makes Passive Houses work.

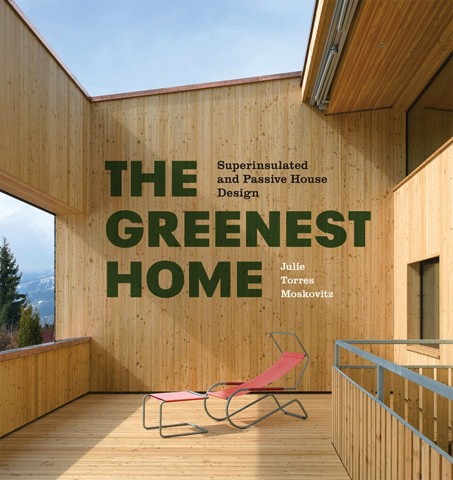

Along with the diversity of locales and demands, there’s some aesthetic diversity—notably the French Bamboo House—but more aesthetic diversity would be welcome. It’s all contemporary minimalism, more or less, and as I leaf through I’m left with an overwhelming sense of stark rectangles. Torres Moskovitz told Dwell that the owners of her Brooklyn brownstone “don’t like anything organic. Only concrete and steel.” For people who do like organic things, other houses in the book show off woody minimalism. (See front cover, above.) I wonder how many readers may turn away from PH because they think it bans people whose tastes run toward maximal, traditional, curvy or quirky.

There’s an excellent chapter on forerunners of the PH movement, back before the term was coined. You’ll find a gorgeous curved house there, thanks to Frank Lloyd Wright.

The main body of the book takes the 18 designs one at a time. This compartmentalization incurs some drawbacks. On the one hand, details that most of the designs have in common are repeated many times. On the other, on details where they diverge—for example, ground-source versus air-source heat pumps—she doesn’t zero in on the difference, or analyze the relative merits.

Another example: several of the houses have “smart” vapor-permeable envelopes, whereas the alternative, a waterproof envelope, is described as “cutting edge” in a chapter on a house that takes that route. I would appreciate some exposition of these opposing ways to address the threat of condensation in walls, which is an albatross skeptics often try to hang around the neck of the PH movement.

As a science writer, I sometimes have to laugh at the ways architects stretch word meanings in an effort to make designs sound radical. In this book a house that has almost enough solar panels to make Net Zero is “virtually off-grid.” Is that like being a little bit pregnant? Excuse me, but the house is on-grid. Another house’s walls are called “fixed sunshades.”

Just as often, though, glimpses come through of the author’s passion for the urgency of greener architecture. Her epigram, an opening salvo from Raymond Dasmann, says “We must . . . comprehend our relationships with the total biosphere upon which our future depends.” It’s a great point of departure for the book.

Princeton Architectural Press gives a publication date of May 15, 2013. 8.5 x 9 inches, hardcover, 192 pages, list price $45.