The Aleutian Housing Authority is in the business of providing low-cost housing for islanders—people often called Aleuts, but Unangan in their own language. The AHA realized they could save a lot of money over the long haul by breaking out of the low-gabled-boxes mode and looking for innovative net-zero-energy, net-zero-water designs. So they held a contest.

Seattle’s Cascadia Green Building Council, originators of the Living Building Challenge, teamed with them, and called it the Living Aleutian Home Design Competition. The first-place design would become a home for one Jimmy Prokopeuff on the island of Atka, but would likely be more or less replicated many times over.

The contest specified 3 bedrooms, 1,150 to 1,350 square feet, budget under $400,000, and, critically, meeting the Living Building Challenge standards—net Zero or better.

I can safely say that each competing architect found challenges here that they had not experienced before. It’s a remote island with no public power or water, so rainwater collection and electric power generation were de rigueur. All materials, even gravel and wood, would have to be shipped in, making the $400,000 target much harder to hit. (That’s what “low-cost housing” means here.)

Atka is not a place of cold extremes. It is exactly as far north as southern Ireland, and similarly awash in an ocean current from the south. It is an extremely windy place, relentlessly chilly, damp, and gray, with no cooling degree days to speak of. From that you can infer several design elements: wind-shedding roofs without eaves; passive solar heating through windows; wind turbines rather than solar panels.

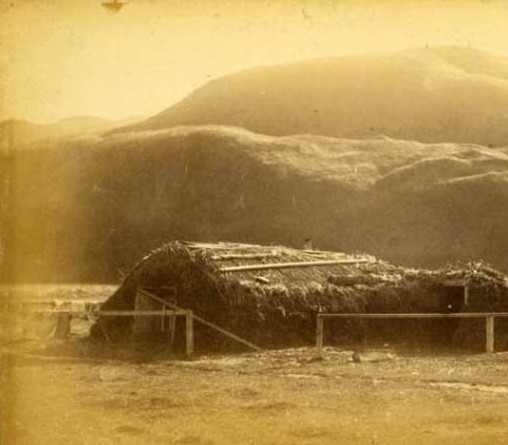

The people fish and hunt. The traditional Unangan dwelling, a barabara, was an elongate pit with an arched roof of sod over driftwood or whalebone. (No trees on the island. I guess sod is an available local material, but none of the awarded designs are sod-covered.) The architect who did the most homework echoed that structure with an arched roof and earth berms pushed against the lower walls. The berms, for geothermal insulation value, seem like a good idea, but the other winning designs preferred to elevate the houses on posts to minimize disturbance to the soil.

Three of the six awarded designs echo the barabara shape in different ways. One is simply a Quonset hut shape. The first place team, Finnesko 13 (along with two of the other five awardees) is from Spain. Long, rounded, sleekly clad in shiny metal, their house comprises lightweight panels that can be assembled on the mainland and shipped in. It uses geothermal heat—presumably a heat pump, since the house is up on posts. (The islands are volcanic, but I have seen no information on whether they are hot at modest depth.)

Janus Welton’s bermed, arched design tied for third place. She recently posted an interesting article on how her archeological research came up with many unexpected strictures, some based on the current lifestyle and others on logistics. For example, while the contest specified one bathroom it was best to separate the lav from the shower for privacy, because Atkaites (currently numbering only 48) commonly take in house guests from other islands, who sleep on the floor for days or weeks at a time while awaiting opportune weather for sailing back home. Also the island’s docks and boats can’t bring in anything too big to strap onto a pallet, so big rainwater cisterns are out. Groups of rain barrels are used. Fortunately perhaps, there is no prolonged dry season.

Welton wanted vegetable gardens to enhance nutrition for these fishing people, but learned that Atka is overrun with non-native rats which make normal gardening impossible; so she incorporated a greenhouse into one end of the house. Lined with metal, I hope.