There are some green building designs that are so simple, you wonder how the world functioned before they were dreamed up. Then there are those that fall under the Rube Goldberg variety that seem needlessly complex, but are based on such a clever principle that you end up forgiving the excesses. This bizarre design for a shifting, “breathable” building façade definitely fits under the latter category.

Conceived by Catalan architects Adrià Escolano and Maria Ubach, the moveable façade, called Active Gallery, is based on the fundamental hydrologic cycle, in which liquids are heated and converted to gases and then condense back to liquid form when cooled. The façade, made of numerous enclosed chambers, harnesses this energy, which drives the opening and closing of the outer skin, requiring no outside source of energy.

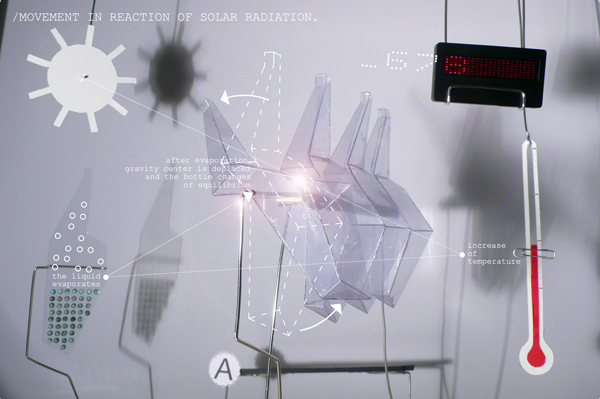

Here’s how the prototype works: A building is constructed with a skin made entirely or partially of a series of interlocking, liquid-filled plastic chambers, each measuring roughly 35 x 12 x 10-inches. These custom-designed, transparent chambers are hung on a steel frame and allowed to pivot individually. The weight of the liquid inside the chamber holds each unit down so that they all form a seal against the outside elements.

Then, as sunlight hits the façade, the liquid begins heating up to a carefully calibrated point where it turns into a gas. As more of the liquid reaches its pre-determined boiling point, the weight of the water at the bottom is transferred to the rest of the interior volume, and the chamber begins to shift as its center of gravity changes. This movement creates small openings in the building envelope, creating ventilation spaces to draw in air and help cool the interior. As the sun sets, the process is reversed, the liquid condenses on the bottom and the chambers all snap shut again.

In effect, the walls of this Active Gallery prototype act as a large, networked thermostat, reacting instantly to temperature changes within the building. Depending on the intensity of the sunlight, the size of the openings can vary from place to place along the envelope of the building, controlled by nothing more than solar energy, equilibrium and the laws of physics.

The prototype, says Escolano, is designed to work best in warm Mediterranean climates that have strong sun almost daily. In these regions, traditional glass courtyards and atriums tend to have serious problems with solar gain during mid-day. So don’t expect to see many of these Active Galleries in the frigid northern climes.

Escolano and Ubach developed the final prototype based on research conducted at the Barcelona Institute of Architecture, one of the more active Spanish institutions experimenting with solar technology. Escolano created a video to demonstrate the principle, but it winds up being a bit too artsy and muddled to add much in the way of explanation.

Suffice it to say that, despite the strange execution, the Active Gallery is an idea that’s crazy enough that it just might breathe new life into the right green building application.