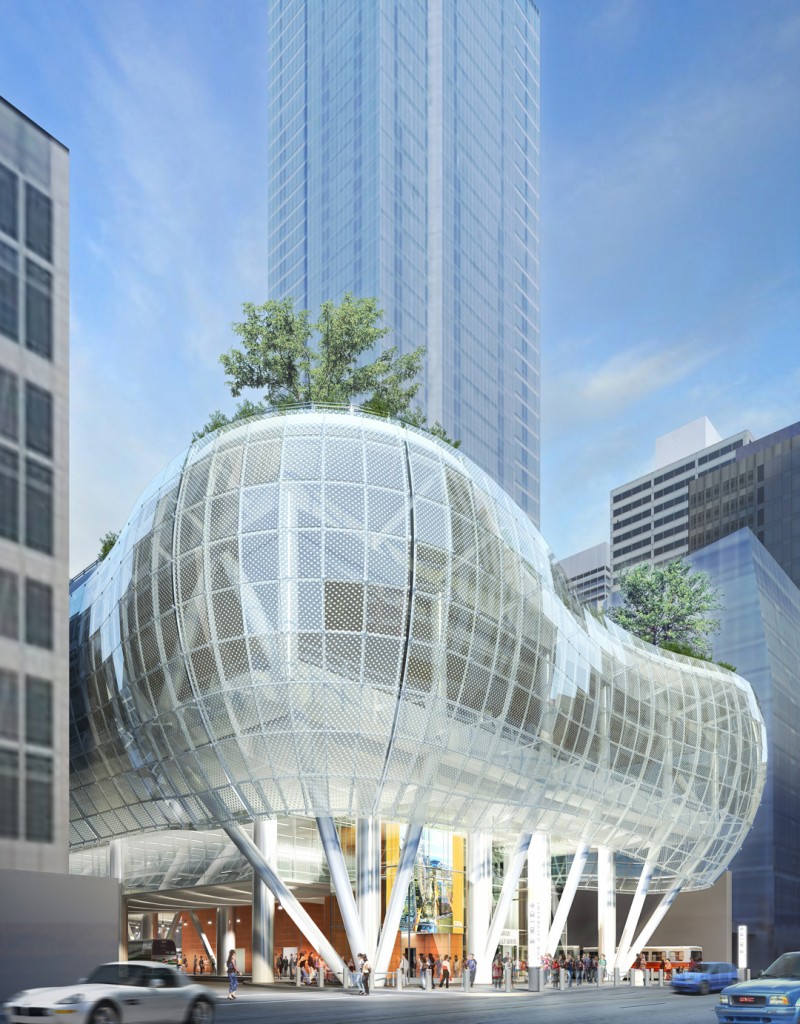

We’ve looked at drawings of a lot of splashy futuristic structures, but here’s one that’s actually under way as a grand public space in an American city: San Francisco’s Transbay Transit Center, a transit hub for 11 different public transit modes.

Aside from the undulating glossy facades, the most striking feature is the roof, a green public park with native-plant gardens, footpaths, cafes, an amphitheater, playgrounds, and a fountain running most of the structure’s four-block length. That sits on top of four levels of transit access.

The structure aims for completion in 2017. If all goes well, high-speed train service from it to Los Angeles and Anaheim will begin the following year.

It’s no surprise to see San Francisco taking a lead in mass transit public works. It ranks fourth among U.S. cities in public transit use—the only city in the top nine that is west of the Appalachians. (It’s still the heart of a sprawling megalopolis where millions commute great distances by freeway; but it benefits from enclosing only a dense core within its city limits.) It’s also a wealthy city.

Still, you may ask how a glamorous new transit center gets funded in a time of constricted budgets. Answer: largely by selling adjacent long-abandoned freeway property, which is made all the more more valuable by building the transit center.

Exactly who is building what skyscrapers within this 40-acre mixed-use project area remains undetermined, but there are likely to be supertalls. A set of five needle-like towers by Renzo Piano was bandied about originally, but then dropped. The main one, Transbay Transit Tower, will be a smooth 1,070-foot sire, the tallest in San Francisco. You can also see sketches (for other parts of the project) of undulating curvaceous towers by Skidmore Owings and Merrill, with wind turbines on a cutaway top.

The transit center proper, designed by Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects along with the TBT Tower, aims for LEED Gold certification. PCPA is a global firm based in New Haven, Connecticut. Rana Creek Living Architecture consulted on the greenery as well the rainwater and graywater systems, while Peter Walker of Berkeley (trans the bay) designed the park.

The center would rate as very green regardless of its actual performance as a structure, so long as it contributes to moving people around much more efficiently than cars do. With verdure and curves like these, that looks like a safe bet.

Time will tell whether the rooftop park ends up as popular as the concourses below. “There’s a lot of skepticism about it,” according to urban design critic John King. “It may be too large and divorced from the city to really work.