Goodness, the anti-solar crowd loved that Associated Press story on solar photovoltaics manufacturing and hazardous waste, the one that purported to expose solar’s “dirtier side,” as the AP called it.

In the Twitterverse, the story became definitive proof that solar is a “scam,” an “environmental nightmare” and, by the way, did you know that “eco hippies are destroying the earth” with PV? Some media outlets did their best to make sure the rabble were fully aroused, led by TheBlaze website, which said solar doesn’t just have a “hazardous waste problem,” but a “big hazardous waste problem.”

We all understand that solar panels need to be disposed of, but does that mean the solar industry has a big hazardous waste problem?

Well, does it?

That’s a complicated question to answer because many people reacting to the article are jumbling two separate issues: solar PV hazardous waste on its own; and the impact disposing of that waste might have on solar PV’s carbon footprint.

That said, the AP article, ultimately, focuses on the carbon footprint question, and on that count, the careful, research-based assessment given to me in an interview by Garvin Heath, who has been at the heart of an effort to make sense of the huge body of research into the greenhouse-gas emissions of different energy technologies, leads me to believe solar is just fine.

But before we get deeper into that, let’s back up for just a second more and fully unpack the AP story. It was long – 1,296 words by my count – but it gave readers just a couple of discernible takeaways: that disposal of hazardous waste produced in the PV manufacturing process has not been counted in life cycle analysis of the technology, and that when it is counted, PV’s value diminishes significantly.

The AP in a few instances credits this one-two punch to “scientists” or “analysts,” but the lone scientist named and the one who offers anything resembling specificity is Dustin Mulvaney, who is described as a San Jose State University professor “who conducts carbon footprint analyses of solar, biofuel and natural gas production.”

Heath, a senior scientist in the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s Technology Systems and Sustainability Analysis Group, said the AP article didn’t include “a lot of information to look at,” but added that he and his colleagues did find “there was one statement that was fairly specific.” That was Mulvaney’s assertion that including disposal of hazardous waste in the life cycle analysis of solar PV “could add 5 percent to a particular product’s carbon footprint” if the waste from the product had to be hauled 1,800 miles for disposal.

That’s the money quote in the piece, my friends, and you really need to think carefully about it. What Mulvaney is saying is that in the relatively rare instances where solar PV waste have to be hauled great distances – we know it’s rare, because according to the AP story, 97 percent of California solar PV hazardous waste stays in the state – the life cycle greenhouse-gas emissions are increased by 5 percent.

Five percent.

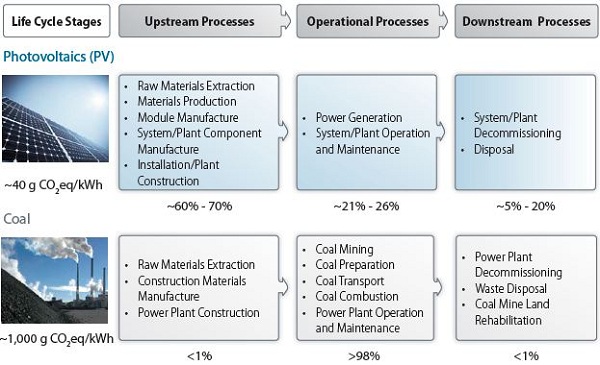

Let’s put that into context: After looking at hundreds of studies, Heath and his colleagues determined that through its various life cycle stages – upstream processes, operational processes and downstream processes – PV emits around the equivalent of 40 grams of CO2 per kilowatt-hour of electricity produced. Coal: 1,000.

Did you get that? It’s 40 vs. 1,000.

So go ahead, add 5 percent to PV. That takes it from 40 to 42.

So now it’s 42 vs. 1,000.

“Context is vitally important,” Heath said. “Sometimes an impact looked at narrowly might seem significant, but seen in the scheme of things, it might not be a big a deal.”

As in this case.

Editor’s note: This article was updated shortly after publication to make clear that solar PV hazardous waste on its own, and the impact disposing of that waste might have on solar PV’s carbon footprint, are two issues best dealt with separately in trying to determine if solar PV is a “clean” technology.