Sure, it’s cool that you can use 3D printing tech to fabricate, oh, say, that cute little wearable planter around your neck. But the future of 3D printing is bigger than that. Much bigger. Say, the size of whole house.

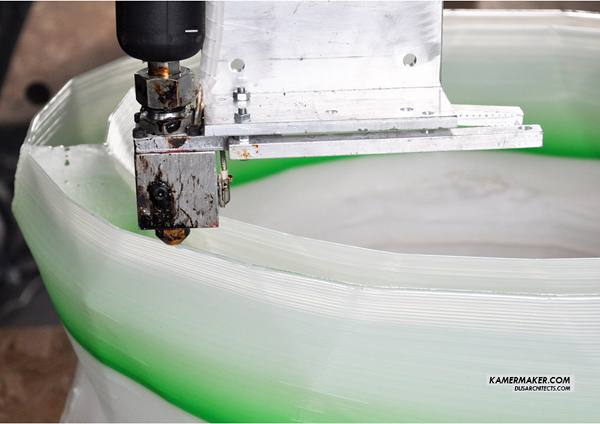

On September 16, the Dutch architecture firm DUS unveiled the KamerMaker, which it has dubbed “the world’s first movable 3-D print pavilion.” Fast CoExist reports that it’s the bigger, badder brother of DUS’s previous version, the Ultimaker, and it can spit out objects as large as 7.2 feet by 7.2 feet by 11.4 feet. That’s plenty big enough to print furniture on site, or perhaps even a room. In fact, what is believed to be the world’s first first entirely printed 3-D room will be finished by the KamerMaker this fall.

Such technology stands to revolutionize building and architecture, among other industries. Using a machine like KamerMaker, anyone who knows their way around CAD could, conceivably, build a house, piece by modular piece, then assemble the thing in one fell swoop, much the way prefabricated home companies like Blu Homes do. Such uses are still pretty futuristic, as far 3D printing goes, as the KamerMaker only prints objects made out of PLA, a kind of bioplastic made out of corn. But as the technology is refined, we can certainly expect to see 3D printed structures making their way into green building.

KamerMaker is a distinct step toward that future in that it’s a pavilion itself — so, as its makers point out, it’s big enough to fabricate other pavilions. Such structures will likely allow architects to push the boundaries of art and architecture for event pavilions, creating structures optimized to capture solar energy, like the Endesa Pavilion in Barcelona, or even fascinating shell structures inspired by nature, such along the lines of Germany’s Bowooss Pavilion.

Another scenario where 3D-printed structures could prove handy is disaster relief. Unlike solar carports (such as this one from Envision Solar) or even disaster housing made of shipping containers — such as the Solar Powered Adaptive Container for Everyone (SPACE) from Houston, Texas, or the United Green Space concept from East Hampton, New York — such structures could be fabricated easily on site, and to the specifications required by different circumstances. (Temporary housing in a flood-zone, for instance, might take a different shape than temporary housing going up after a tornado.)

Of course, 3D-printed structures lack the benefits of buildings that are shipped with solar power and rainwater harvesting built in (and, in the case of Japan’s Mirai Nihon house, every other self-sufficient, off-grid amenity under the sun). But 3D-fabricated disaster housing could easily be adapted, on site, to utilize whatever self-sufficient resources may be available.

All of these big potentials for 3D printing may sound pretty futuristic, and in some ways they still are. But the KamerMaker represents the realization of some of those big potentials — and while there are no immediate plans to commercialize the tech behind it, DUS currently has the printer open for use by the public four days a week in Amsterdam. Next year, it will set off on a tour of the Netherlands.