Whether there was a national security risk posed by a pair of big-time Chinese executives owning a cluster of tiny wind farms under development near a Navy weapons training facility in northeastern Oregon is difficult to say – but it probably wasn’t hard for the man seeking reelection to see the political risks.

President Obama on Friday moved to swiftly dispense with a case that mixed China, renewable energy, trade and defense into a giant, complex ball of trouble; he ordered Ralls Corporation, owned by the chief financial officer and the vice president at the large but not state-owned Chinese manufacturing conglomerate Sany Group, to divest itself of the wind power projects.

This is the first time a president has used his power in such a fashion since President George Bush – the first one – stopped the sale of Mamco Manufacturing to a Chinese agency in 1990.

In an executive order, Obama said “there is credible evidence” that led him to believe that Ralls “might take action that threatens to impair the national security of the United States,” but he gave no specifics.

The president stepped in after the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) had raised red flags about the Ralls purchase, this past spring, of the projects, which consisted then of everything that comes before wind turbines actually go up at a site: land rights, permits, easements, interconnection agreements, a power purchase agreement (with PacificCorp), etc.

CFIUS is a panel headed by Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner and consisting of the heads of a range of federal departments, Homeland Security, Energy, Justice, State, Treasury and Defense among them. By statute [PDF], the panel can review foreign acquisitions of U.S.-based businesses to ensure the transactions pose no threat to national security.

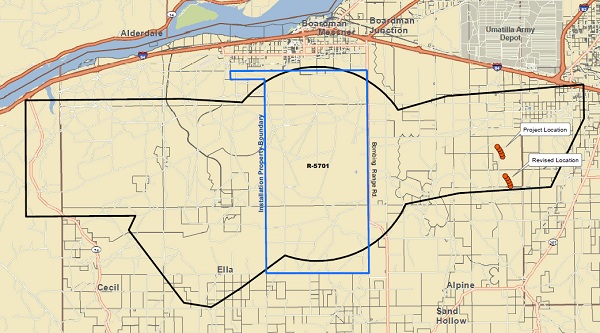

The Oregon wind farms – four of them, each with five 2-megawatt turbines, adding up to 40 MW of generating capacity – had been under development in Morrow and Umatilla counties near the Naval Weapons Systems Training Facility Boardman, and one of them was in the facility’s restricted airspace, called R-5701, on its east side.

This region of Oregon and Washington state around the Columbia River, a couple of hours or so east of Portland by car, is thick with wind farms. In fact, the massive 845-MW Shepherds Flat wind farm that went into full operation just a week ago borders the Boardman Navy test area on the west side, with some of its 334 turbines running right up to the edge of the restricted air space, if not into it.

The Navy has acknowledged it does unmanned aerial systems operations training at Boardman, and a Navy letter [PDF] to the Oregon Public Utility Commission mentioned that R-5701 is the “only restricted area in the Western U.S. in which EA-6.8 Prowler and EA-18G Growler fighter jets based at Naval Air Station (NAS) Whidbey Island (Wash.) can complete Low Level Tactical Training and Surface-to-Air Counter Tactics maneuvers.” The Navy said such maneuvers are conducted “to within 200 feet above ground level.” Turbines towers are often 80 to 100 meters tall, with the spinning blade tips reaching much higher than that.

Court and Oregon documents [PDF] indicate Ralls worked with the Navy to move the site of one of the wind farms 1.5 miles – from the middle of the Navy’s restricted airspace to inside the southern edge. According to the Navy, until 2009 it had been able to count on the Federal Aviation Administration to keep wind farm developers out of its hair. However, “(s)tarting in 2009,” the Navy said, “the FAA determined the issuance of a Notice of Presumed Hazard for proposed construction within a restricted area was not appropriate and started issuing a Determination of No Hazard for proposed construction within R-5701.”

The Navy, with little leverage to force the wind farm completely out of its space, supported this move in a letter to Oregon regulators. Nonetheless, CFIUS ordered a halt to work on the projects, called High Plateau, Mule Hollow and Pine City, in addition to Lower Ridge, the one that Ralls had shifted to try to satisfy the Navy. (Together Ralls has referred to the wind farms as the Butter Creek projects, which aren’t to be confused with Butter Creek Power, a separate 4.95-megawatt Oregon wind farm that began operation in 2009.) Ralls went to court to try to overturn the CFIUS order, and made a number of interesting assertions in its complaint [PDF]. First, it said it had no interest in owning the wind farms long-term, and only bought them in order to make sure that Sany Electric Company wind turbine generators were used in the projects. And when Ralls told CFIUS that it was in talks to sell the projects – believing this would “address CFIUS’s concerns” – CFIUS amended its earlier order to add that Ralls couldn’t sell the projects [PDF].

Ralls, meanwhile, was eager to get the work done – which brings up another fascinating point: Ralls said in court documents that the project needed to be completed and operating by Dec. 31 in order for the company to take advantage of “approximately $25 million in federal renewable energy investment tax incentives.”

Federal law now allows wind developers to claim an investment tax credit, equal to 30 percent of the cost of a project, in lieu of the production tax credit for wind. But like the PTC, the ITC is set to expire at the end of the year. (It’s possible, too, that the project was far enough along by Dec. 31, 2011, to meet the “safe harbor” provisions of the now-expired Section 1603 program, which allowed developers to take the ITC as a cash grant instead of tax credit.)

These facts only seem to heighten the political dilemma the White House faced. With his opponent talking tough on China these days, did President Obama really want to allow a wind farm near a military installation go into Chinese ownership – with the possibility that all four wind farms (small though they might have been) might use Chinese components? And then the developer would be rewarded with a $25 million check from the U.S. Treasury when it was all done?

Fox News might have seen a story there.

In a statement, Ralls, which has 90 days to divest itself of the wind farms, noted there were “scores of other wind turbines (that) already operate in the area” where it was building. The company said it would fight the president’s decision in the courts.