It ain’t all solar panels, wind turbines and algae oil, people. Among the clean-energy developments the Obama administration is encouraging – part of the $90 billion that Mitt Romney says the president has “invested in so-called green energy companies” – is a big program that would, in effect, allow for the continued burning of coal and other fossil fuels.

Howzat? It’s called carbon capture and sequestration. Some $3 billion of Mitt’s $90 billion is being poured into this broad category, according to the White House. And this week, the U.S. Department of Energy announced that carbon dioxide injecting had begun at “the world’s first fully integrated coal power and geological storage project,” in southwest Alabama.

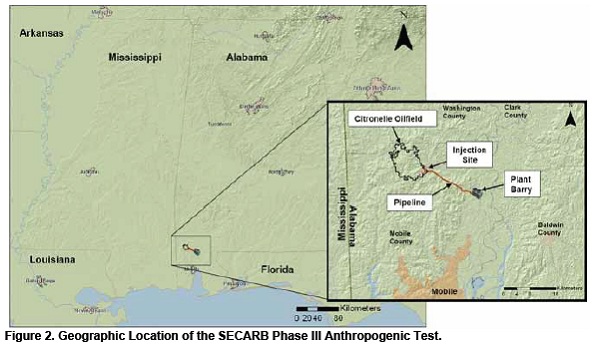

The government’s Regional Carbon Sequestration Partnership program has been moving forward with a number of projects to test the viability of capturing and storing greenhouse gases, but this is the first go at an “anthropogenic test” – one using man-made CO2 from a coal-fired power generating plant. The project, in partnership with Southern Company, is receiving $30.3 million in support from the DOE.*

If all goes as hoped, the CO2 that’s captured and stored could be used for what’s known as enhanced oil recovery (EOR), in which the CO2, in a liquid or “supercritical” state — in which it behaves somewhat like a gas and a fluid — is pumped into deeper mineral formulations to drive out oil. If getting more oil out of the ground doesn’t sound green, the logic is that doing so using EOR will minimize the need for new drilling on protected lands, while at the same time reducing global warming pollution by sequestering large amounts of industrial-produced CO2 undergound.

At the Alabama project, the carbon dioxide being used originates at the 2,657 MW Barry Electric Generating station in Bucks — Plant Barry, as it’s known. A relatively small amount of the flue gas – equivalent to that produced from 25 MW of electrical generation – is being captured. According to the DOE, a process developed by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries is turning this flue gas into “a nearly pure stream of CO2.” The Mitsubishi process is newly developed. A solvent is used to capture a large portion of the CO2 — 90 percent, according to the company — while doing so “with significant reductions in energy penalty from current technologies,” according to a September 2011 presentation [PDF] from the project’s developers.

The CO2 goes in a pipeline, constructed last year, and moves 12 miles west to a geologic structure called the Cirtonelle Dome, “which provides secure four-way closure free of faults or fracture zones.” One of the chief concerns with these underground CO2 storage schemes – which got big play after a 2010 Duke study [PDF] – is possible groundwater contamination. But the DOE says the Paluxy Formation, a reservoir some 3,000-3,400 meters below ground where the Plant Barry CO2 will go, “is too deep and salty to serve as a drinking water supply.”

*This story originally reported the DOE contribution at $295 million, citing a U.S. Department of Energy press release from 2009. However, because the scope of the Plant Barry project changed, the DOE contribution also changed. In an email to EarthTechling, Southern Company spokesman Marc Rice said the DOE contribution to the project was $30.3 million, with a $9.5 million contribution from Southern Company and industry partners. A document [PDF] from the Southeast Regional Carbon Sequestration Partnership, updated January 23, 2012, puts the total cost of the Phase III development part of the SECARB program — which includes the Plant Barry “Anthropogenic Test” and a separate but related ongoing “Early Test” that does not involve Southern Company — at $111,413,431, with the DOE share at $76,981,260.

Carbon capture has captured significant but far from unanimous support among environmentalists. The National Resources Defense Council is wildly enthusiastic about it, seeing it as a chief tool in the fight against climate change, but Greenpeace not long ago put out a report announcing the demise of carbon capture. Among the problems it cited: prohibitively expensive costs; huge energy intensity required in the capture and compression process; the lack of safe-storage certainty; and limits to storage capacity.

The Sierra Club is somewhere in between. It has a bit of a wait and see view, saying “right now, there are no commercially available or widely demonstrated technologies including carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) that make it technologically possible or financially feasible to burn coal without accelerating global warming.”

With the Alabama project, by injecting 550 metric tons of CO2 per day – 100,000 to 150,000 tonnes per year — for two years, and monitoring what happens in and around the site for three years afterward, the DOE hopes to gain insight into the technological possibilities.

But that will still leave the financial feasibility up in the air. A recent International Energy Agency study [PDF] estimated costs of power plants with CO2 capture to be “74 percent higher than the reference costs without capture,” and Greenpeace, in its critique, said the capital costs of coal plants with carbon capture “would be 2 1/2 times that of concentrating solar power and more than 4 times that of wind power.”