Here’s a highly technical study with an easy-to-digest result: “the bigger the wind turbine is, the greener the produced electricity is.”

This is good to know, since, as we reported only earlier this week, turbines are getting bigger, especially offshore wind turbines.

This new study’s authors, from the Institute of Environmental Engineering in Zurich, say that the turbine industry has gotten to the point where manufacturers have the “knowledge, experience and technology to build big wind turbines with great efficiency,” according to a release by the publisher ACS.

In addition, “advanced materials and designs permit the efficient construction of large turbine blades that harness more wind without proportional increases in their mass or the masses of the tower and the nacelle that houses the generator.”

Indeed, in unveiling its 75-meter-long B75 Quantum Blade earlier this month, Siemens noted that “if the B75 Quantum blade were produced using traditional technology, it would be 25-50 percent heavier. Heavy blades are subject to higher loads and require stronger nacelles, towers, and foundations. The combination of intelligent design and low weight has a correspondingly positive effect on the power generation costs for wind energy.”

According to the researchers, these bigger turbines are able to produce more wind power without large increases in the amount of material needed for construction or fuel needed for transportation. As a result, “for every cumulative production doubling, the global warming potential per kWh (kilowatt-hour) was reduced by 14 percent.”

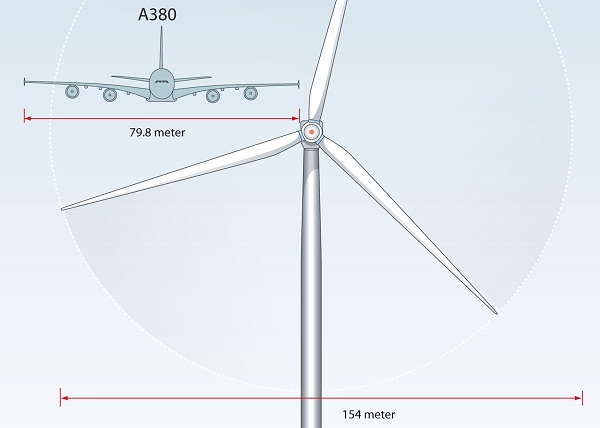

The researchers in Switzerland, whose work was written up in the journal Environmental Science & Technology [PDF], pointed to studies showing that “the average size of commercial turbines has grown 10-fold in the last 30 years, from diameters of 50 feet in 1980 to nearly 500 feet today.”

How big could turbines get? “On the horizon: super-giant turbines approaching 1,000 feet in diameter,” the ACS release speculates.

One other thing about the study that deserves mention is that it focused on land-based turbines, where the larger-size trend isn’t as pronounced as with offshore wind power. On land, turbines at big wind farms are usually in the range of 1.6 to 3 megawatts (MW), with rotor diameters around 350 to 375 feet. In part this is because the bigger turbines need more space, not just for their longer blades but also in order not to avoid wake effects.

The authors acknowledged this in the study, but said “the boundaries of the study were set by a single wind turbine and not a wind park…. The land use impact results in this study are therefore limited to standalone wind turbines only.”