The story of rooftop solar power in recent years is one of challenges conquered. Panels too pricey? Scaled up production (in China, mainly) took care of that. System capital costs still too high? New finance models, like leasing, came to the rescue.

The next big challenge to fall by the wayside might be in making solar available to the millions of people and businesses who don’t have a rooftop of their own for a system.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory just released a report that found massive potential for shared solar, aka “community solar” or “solar gardens.”

Shared solar can be done a lot of different ways, but one common model is for a developer to build a project in a good location – a sunny open lot, for example. Local residents are then invited to subscribe to a portion of the project, paying a relatively cheap and stable price for credits that offset their electricity use on their monthly utility bill.

NREL said just shy of half of all households can’t do solar, either because they don’t own the building they live in or their roof isn’t right for solar. It’s a similar situation for businesses. But:

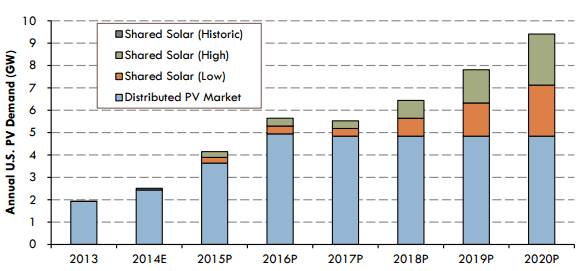

By opening the market to these customers, shared solar could represent 32%–49% of the distributed PV market in 2020, thereby leading to growing cumulative PV deployment growth in 2015–2020 of 5.5–11.0 GW, and representing $8.2–$16.3 billion of cumulative investment.

As of the beginning of this year, the U.S. had 18.3 gigawatts of operating PV (residential, utility-scale, you name it) – so a whole new market of 5-11 GW over the five years would be huge.

What will it take to make this happen? A regulatory mechanism – “virtual net metering” or a set valuation or “tariff” for solar – is a top prerequisite, allowing the typical benefits of distributed solar to be shared. Some states and localities have such regulations in place, many don’t, and the rules are rarely the same from place to place. That makes it hard for business models that can drive big growth to develop, so regulatory standardization is one thing community solar will need in order to reach its potential.

But when the road is opened to solar, folks will drive down it. In Colorado, the first state to enact pro-community solar legislation, there “are 14 operating solar gardens in the service area of Xcel Energy, Colorado’s largest electric utility, with 530 customers participating and 98 percent of the gardens’ capacity sold,” according to the Denver Post.

Big Solar has noticed; late last year, First Solar invested in the Colorado community-solar developer Clean Energy Collective, and more recently NRG Renew agreed to finance five solar gardens that SunShare is doing in Colorado.

But what about utilities, famously antsy about distributed solar? Well, community solar can be a cost-effective way to appease customer demand for more solar, keeping the utility in the game with their customers in a way rooftop doesn’t. At an industry conference in San Diego late last year, Julia Hamm, president and CEO of the Solar Electric Power Association, said interest was growing. “We have 500 utility members and there isn’t one of them who isn’t interested in community solar,” she said.

Which doesn’t mean utilities will always be perfectly aligned with solar advocates on the gritty details of community solar. Xcel, for instance, has embraced community solar in Minnesota in addition to Colorado, but the utility is raising hackles by pushing to limit Minnesota corporate projects that cluster together 1-megawatt arrays, the size limit in the program. Even so, “If the large clusters of projects are excluded, Xcel said it still expects about 80 MW of solar gardens would be developed by the end of 2016,” the Star-Tribune reported.