Forecasts of doom for the California power grid have been popping up since the state began its aggressive pursuit of more renewable energy, and have became more emphatic since the San Onofre nuclear power plant, in Southern California, went offline at the end of January 2012.

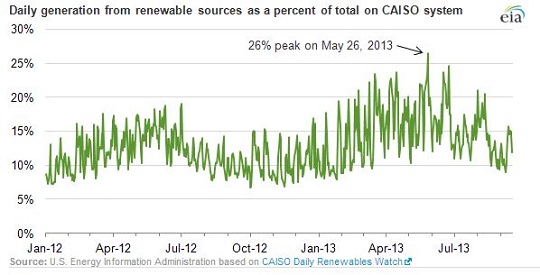

Now two summers have passed and fresh data shows renewables assuming an ever-growing share of the state’s energy generation – at times providing more than one-quarter of a day’s output. But so far, no doom.

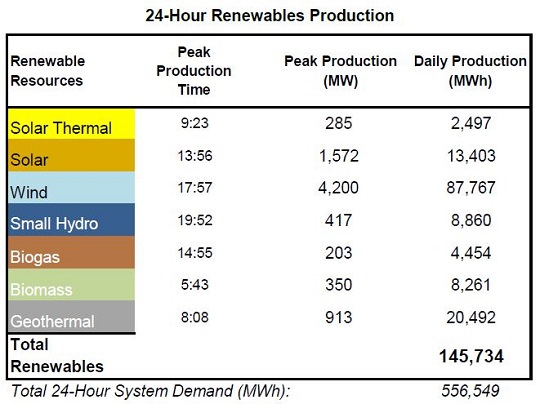

As cited in a new U.S. Energy Information Administration report, on May 26 this year, total 24-hour demand on CAISO, California’s main grid system, was 556,549 megawatt-hours. Renewables – and here we’re not counting large hydro – totaled 145,734 megawatt-hours. That’s 26 percent of all the energy used on CAISO.

And here’s another fact that should make renewable energy fans feel good: These totals don’t include what’s known as “behind-the-meter” energy generation, the stuff from rooftop solar systems (and a few wind turbines here and there) on homes and businesses that cut into the amount of energy the utilities need to serve. The California Solar Initiative has helped put more than 1,600 megawatts of solar capacity behind meters.

With the June decision to shut down San Onofre for good, it’s clear that renewable energy will only become a more important piece of the California energy puzzle. May 26 demonstrates that renewables can produce a lot of power, but according to Tyson Brown, who prepared the EIA analysis, renewables aren’t the full story behind California’s success in meeting electricity demand for the past couple of years.

“They have been adding a lot of solar and wind, but they’ve also done a lot of transmission upgrades and additions of natural gas generation,” Brown said in an interview. The role of natural gas is a bit ironic; as distasteful as many greens find it, the availability of cheap natural gas, which can ramp up to meet demand when intermittent renewable sources fall off, has clearly made it easier for California to ease more renewable energy onto the grid.

Brown also noted a demand-side factor to California’s success so far in keeping the lights on. “There haven’t been really big demand increase,” he said. People often attribute that to the relatively slow economic recovery, but Tyson notes that another crucial factor has been that California utilities have been “very, very aggressive” in tamping down peak demand through energy efficiency and demand-side management programs.

That makes sense, since, in the end, that’s the key obligation for utilities: meeting that peak demand. And that’s why more solar would seem to be exactly what California needs to avoid trouble in the years ahead, when the pessimists think grid problems really could arise. Sure, looking at the levelized cost of energy, solar isn’t as cheap as wind, but as Brown pointed out in our interview, the real cost of energy is highly dependent on when it is available. On the hot summer afternoons when the California grid is under the most pressure, wind tends to be at low ebb, while solar can still be making a significant contribution. For California’s grid security, the more solar, the better, it seems.