Let’s add one more thing to the list of potential stumbling blocks for Chokecherry and Sierra Madre, that ginormous Wyoming wind farm project. It’s a little guy, weighing in around 2 to 7 pounds – but it could pack a wallop.

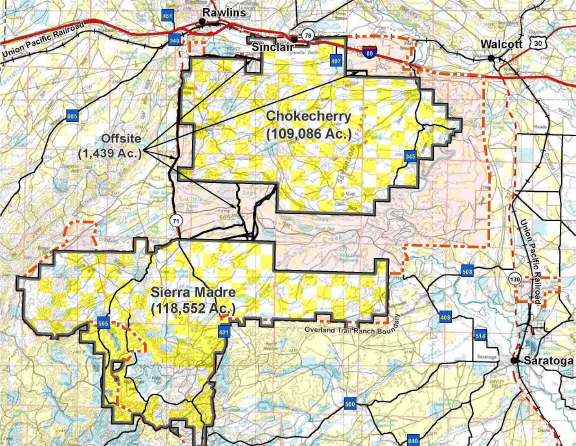

The Obama administration last week approved a Carbon County, Wyo., site as appropriate for development of the wind farm, which could consists of 1,000 turbines. Environmental groups, however, say the area is prime habitat for the greater sage grouse, a ground bird that the federal government calls “an icon of western sagebrush ecosystems” and that is under consideration for Endangered Species Act listing.

Project developer Power Company of Wyoming (PCW), a subsidiary of Anschutz Corporation, said in an email to EarthTechling that none of the development would take place in state-designated sage grouse core areas, and that the project “includes full compliance with the terms of the Governor’s Executive Order regarding development in non-core areas.”

In its approval announcement, the Department of the Interior said “the project will avoid Sage-Grouse Core Areas through a conservation plan that accommodates ongoing ranching and agricultural operations…. Permits to build the project will be provided on a phased basis, and will be contingent on implementation of wildlife protection measures.”

Nevertheless, in a press release, the Wyoming-based group Biodiversity Conversation Alliance denounced the site approval.

“Choosing this site for green energy was a terrible mistake,” said Barbara Parsons, who served on the South Central Sage-grouse working group, formed by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department in 2004 to develop conservation plans for the bird in the region where Chokecherry and Sierra Madre is planned. “When one thousand concrete pads and the connecting roads are built, this prime wildlife habitat will be permanently erased from the landscape.”

Parsons maintains that in 2008, “bullying and cajoling and twisting arms” by Anschutz “got the Core Area changed to exclude the lands where they wanted to build wind turbines.”

The spinning turbines pose no direct impact threat to the bird, of course, but the evidence from oil and gas development in its habitat shows the sage grouse to be highly sensitive to the presence of man-made structures. “Sage-grouse populations typically decline following oil and gas development, and birds have been displaced from habitat near infrastructure and locations with humans,” a 2009 federal study said [PDF]. “Notably, it has been shown that female grouse nesting in developed areas had lower annual survival rates. Chick mortality rates also were higher within sight of oil wells.”

Last week’s Record of Decision by Department of the Interior Secretary Ken Salazar set the wheels in motion for the U.S. Bureau of Land Management to proceed with site-specific analysis for the project.

The BLM knows a little something about the greater sage grouse. On its website, the agency says “greater sage grouse conservation is urgent,” because “sage grouse have declined in number over the past one hundred years because of the loss, degradation, and fragmentation of sagebrush habitats essential for their survival.”

You’d get no argument there from Erik Molvar, wildlife biologist with Biodiversity Conservation Alliance.

“This project should have been sited on the High Plains to the east of the Laramie Range, where it would have had minimal impacts on rare and sensitive wildlife,” Molvar said.

It’s not just the birds on the ground that environmentalists are worried about. The American Bird Conservancy says Chokecherry and Sierra Madre could be a disaster for golden eagles.

“This project is on track to become the single most deadly wind farm for eagles in the country, an Altamont Pass II,” said Kelly Fuller, wind campaign coordinator for group.

Altamont Pass, east of San Francisco, is the site of an infamous early wind power development that, according to a 2004 study, was found to be killing up to 4,271 birds annually, including between 881 and 1,330 raptors such as golden eagles, which are projected under federal law, as well as hawks, falcons and owls. Under a 2010 agreement with environmental groups, older turbines at Altamont are being replaced and relocated, and a local Audubon Society chapter forecast an 80 percent reduction in impacts to birds.

The ABC noted that BLM estimated 46-64 eagles could be killed at Chokecherry and Sierra Madre each year, but said “other estimates put this figure as high as 215 Golden Eagles.”

On page 2: The company vows carefully siting of turbines

Power Company of Wyoming has said that its extensive analysis of the area will allow it to minimize impacts.

“We have collected more scientific data in a broader area and to a finer degree than anyone else has ever done,” Bill Miller, PCW president and CEO, said in a statement. “We know where turbines should and should not go. Our plan to microsite all turbines will assure potential impacts on wildlife are far lower than outlined in the general project-wide (environmental impact statement), while also materially increasing the country’s clean energy supplies.”

But the Biodiversity Conservation Alliance said a better site was available. Like a lot of environmental organizations (including the American Bird Conservancy), it says it supports wind power as a necessary tool in the fight against climate change — but only when siting is carefully considered. “This project should be sited elsewhere, such as the High Plains to the east of the Laramie Range, where it would have had minimal impacts on rare and sensitive wildlife,” BCA’s Molvar said.

In an article in the Cheyenne-based Wyoming Tribune Eagle, Molvar suggested the group was considering taking legal action against the development.

In addition to the environmental issues, Chokecherry and Sierra Madre faces other challenges: It’s unknown if PCW would push forward with the project if the expiring production tax credit for wind isn’t renewed. Also, the project’s viability is contingent on the approval and construction of a 725-mile power line that would feed the energy produced in Wyoming to markets in the Southwest.