The Passive House concept is said to have come out of a 1988 conversation between a German and a Swede. Research projects were funded, the first Passivhaus (PH) residences were built in 1990, and the Passivhaus Institute founded in 1996.

In fact, the German and the Swede, from day one, acknowledged their forebears—in particular the American William Shurcliff, who published a 1979 manifesto spelling out most of the main precepts of Passivhaus and suggesting possible names for his new concept, most of them including the word “passive.” Pre-1990 structures that were essentially passive houses have recently received much-deserved attention from Julie Torres Moskovitz in a new book and also from Lloyd Alter at Treehugger.

The 10970s OPEC oil embargo sparked a great surge of creative thinking on super-insulated house design. Few people worried about climate change then. People worried about running out of fossil fuels, and about dependence for oil on unstable foreign nations.

Architects came up with the same broad approaches to energy conservation that we use today: much thicker insulation, careful placement for taking in solar heat when it is needed and not when it is not. Some houses from that period were (and still are) very effective.

Many of the 1970s pioneers called their concept “passive solar.” That idea had been around at least since the 1940s, when Frank Lloyd Wright showed it off in his first Solar Hemicycle House. This gorgeously simple Wisconsin house forms a south-facing arc wrapped around a sunken lawn and garden. The northerly outside of the arc is earth-bermed, or partially buried in built-up soil, the ultimate insulation. The sunken lawn area captures heat, protects it from wind, and feeds it into the house. The semicircular shape actually reduces solar gain, but helps with Wright’s design for air flow, which is said to be amazingly effective.

Amory Lovins built himself a famous and beautiful passive solar house in Snowmass, CO, at 8,000 feet above sea level. Completed in 1984, it was heavily updated, with plenty of press coverage, in 2008.

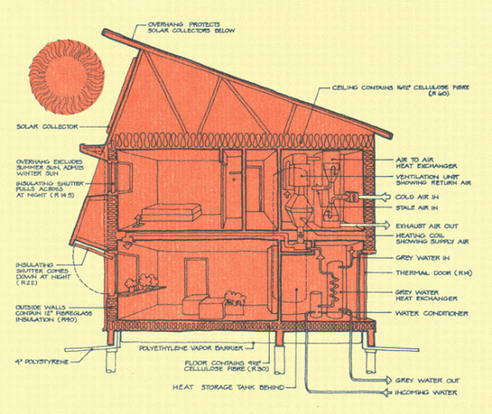

But Passivhaus takes pains to distinguish itself from “passive solar.” An alternative path was marked in 1977 by the Saskatchewan Research Council in designing their Saskatchewan Conservation House. More than 30,000 people came to see this demonstration project when it was open to the public. Then it lapsed into obscurity, while continuing to perform very well as a classic passive house. It is now so obscure that its own owner was apparently unaware that he lives in a house design milestone.

The Saskatchewan House made a break away from “passive solar” and toward still greater emphasis on airtightness. It had big solar thermal collectors on the south, but eschewed big south windows and any structures added for thermal mass. These were directions that Shurcliff celebrated and the Europeans followed later. (I think the departure from passive solar has been exaggerated: careful placement of windows for solar gain remains a huge part of PH. Dramatic thermal mass features are rare, but many PH designers like concrete floors for their thermal mass.)

According to Passipedia, the very first passive house was not a building but a boat, the Fram, which Fridtjof Nansen outfitted for exploring the Arctic Ocean in 1884. He needed to be up there for months at a time without freezing to death, and without frequent trips southward just to resupply his firewood. He succeeded.